We are seeing the future of the construction industry unfold as it is as high-tech as space travel.

In Australia, the industry is vibrant and diverse but, like its counterparts in the rest of the developed world, it is not without challenges and a deep need to change in order to maximise opportunities.

Poor productivity, delays, safety issues and a shortage of skilled labour are just a few of the issues. Increasing project complexity brings significant challenges, say the experts. Errors, miscommunication and misunderstandings increase as all parties involved in a project try to keep track of details on paper and in unconnected software applications.

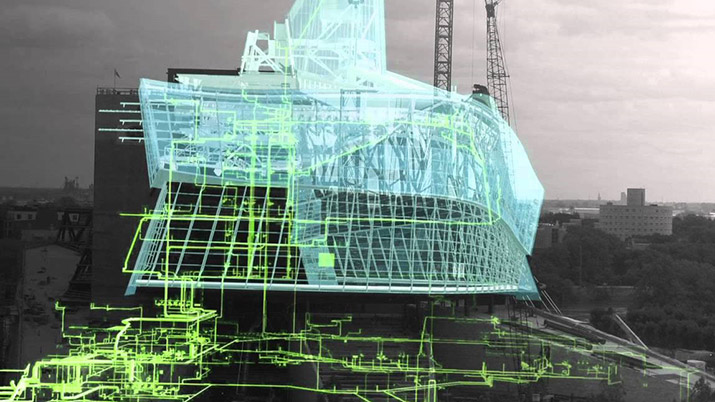

Building Information Modelling (BIM) is being seen

globally as the way forward for the architecture, engineering and construction

industries. Very broadly, it is a digital representation of the physical and

functional characteristics of a building – a digital collaboration between the

software of all firms working on the project and a process for creating and

managing all project information before, during and after construction.

BIM integrates all aspects of a project like never before.

Using BIM, you can visualise the finished building with all its components and all its systems before construction begins. Potential problems can be identified and fixed at this time and physical errors and costly revisions avoided. Owners and contractors can identify, analyse and record the impact of changes on costs and scheduling.

BIM tracks and monitors materials, so this becomes streamlined, highly efficient and waste is reduced. After handover, BIM becomes the basis for maintenance scheduling.

BIM can be used on parts of a project, but to get the full benefit of the technology, owners, designers and contractors need to incorporate it right from the design stage, and all stakeholders need to adopt design and data-reporting formats compatible with BIM. With its ability to minimise waste of materials, time and effort BIM is also a driver in lean construction.

Global software company Autodesk calls this deep connection between physical outcomes and digital systems “the biggest change since the industrial revolution”.

“BIM is rapidly becoming industry standard across the architecture, engineering and construction industry,” says a spokesperson for the company.

Autodesk’s CEO, Andrew Anagnost, laments the state of the construction industry.“We all know [the construction industry] wastes about 30 per cent of its resources on every project. It’s also responsible for about 40 per cent of what we see inside landfills,” he says.

Figures on the uptake of BIM in all its forms in Australia are not available. A survey by Redstack of 150 industry professionals in Australia and New Zealand found that 47 per cent of respondents had completed at least one BIM project, but does not indicate how extensively BIM was used on the projects. Twenty per cent of respondents said they were implementing it and 18 per cent are planning to involve BIM.

Nando Mogollon, professional services manager at Central Innovation, the Australian representative of global software company and ArchiCAD creator, Graphisoft, says that from a historical perspective Australia and New Zealand were early adopters.

“In the late 1980s and ’90s, we were at the forefront of implementing this type of technology. It was not called BIM. It was called Virtual Building. I think we started lagging behind to see what other countries would do. The government take here on it has been slow,” he says.

There seems to be a consensus that adoption has stalled because of the lack of effort to mandate BIM adoption or develop national BIM standards. Other barriers include software incompatibilities among stakeholders on a project; some legal issues are still to be tested; the cost of software; and the lack of experts working in the field.

Timber Building Systems, a Victorian prefab company, was launched about four years ago to be fully BIM literate from the outset. The company uses a revolutionary post tensioned pre-manufactured building system for multi-level apartments, hotels, student accommodation, aged care facilities and commercial buildings.

Tim Newman, General Manager of Timber Building Systems (TBS), had led the development of PowerCad Software’s new REVIT tools and associated BIM workflows, and for most of his career had been an automotive engineer at GM Holden.

“At TBS we are focused on bringing an automotive level of production capability and quality control to the building industry. BIM plays a critical part in making that a reality. Many of the BIM processes the construction industry is adopting are similar to what the automotive industry use, it’s just different terms,” Newman says.

He says the company has a BIM workflow from the initial quote through to the building installation. “This includes structural design, costing and installation plans. All our major production equipment is linked to our BIM models.

“Our BIM processes typically include Autodesk products, but have we number of other interfacing software packages and in-house developed programs. What we are doing at TBS is unique. There is no one package or software provider that covers everything we need.

“We have developed a workflow utilising 3D scanning and a rigid quality process that ensures every panel is built with precision in the factory and installed without any surprises when we get to site,” Newman says.

Melbourne firm Fraser Paxton Architects does a lot of modular work and specialises in SIP (Structural Insulated Panel) House construction and design.

“BIM has been around for ages but the uptake has been a bit slow. I think that’s partly to do with the software and the different ways firms work. The different software permutations and combinations are huge,” says founder Fraser Paxton, adding that the company uses AutoCAD and REVIT.

Paxton says BIM is a natural fit for the modular sector.

“The capacity for BIM to go straight from design to manufacturing cuts out a lot errors. It provides a platform to see errors before they occur.”

“It combines the architectural model, engineering model and services model. Building Information Modelling (BIM) works best when you are dealing with larger buildings. You can see where the clashes are before you get on site. It does work with houses and small buildings, but you don’t have much complexity there,” he says.

He is enthusiastic about the ability to are seeing the future of the construction industry unfold as it is as high-tech as space travel. and modular construction to maximise lean manufacturing and is working on a PhD with the Centre of Advanced Manufacture of Prefabricated Housing at the University of Melbourne looking at lean manufacturing and lowcost housing. “You can really optimise materials usage with BIM.”

BIM is rapidly becoming industry standard across global architecture, engineering and construction industries. Governments in Britain, Finland and Singapore mandate the use of BIM for public infrastructure projects. The Institute of Public Works Engineering Australasia says that “the Federal Government, as well as various state government departments, are intensifying their efforts to promote and adopt BIM.”

The Australian Construction Industry Forum says that “with an estimated construction spend in Australia of $207 billion in 2016-17 it is critical that efficient and effective processes are utilised. For example, a 15 per cent productivity improvement driven by BIM would result in a $31 billion saving. The potential for savings through the use of BIM is estimated at 15-20 per cent per project.”

Glue Laminated Timber manufacturer Hyne Timber is providing Building Information Modelling (BIM) content for GLT in accordance with the AS/NZS BIM standards. It is available for REVIT users.

“All product details, from dimensions, mass and volume, down to the colour and texture of GLT can be brought into the 3D model in a single integrated BIM element. This means we can exchange quantitative information with our consultant team, particularly the structural engineer, as well as clients, all from the same model,” says the proposal’s principal architect Kim Baber.

Dr Rizal Muslimin teaches at the University of Sydney School of Architecture, Design & Planning. He draws a line from the 1800s to the present, and the future, beginning with the object-oriented design catalogue created by architect Jean-Nicholas-Louis Durand from which architects could select elements to put together and design buildings.

He indicates that one problem presented by Building Information Modelling (BIM) is relying too much on the software, with the result that the architect can start to think of the design in terms of how the software is going to produce it.

“Before we introduce the software, we need to outline the history. Before we teach students the tools, they need to understand the philosophy with all the advantages and limitations.”

He says there must be a balance between the design skills and creativity of the architect and the software, otherwise they are going to be thinking of the design in terms of how the tools will produce it. “We need to teach them how to customise, how to develop their own design tools, so they are not relying solely on the software,” he says.

“We want to teach them to be not just technicians, but also contributors to this field.”

He says that in the first phase of widespread use of design software – CAD in the 1980s –the mouse simply replaced the hand in drawing. In the mid-’90s, architects began to customise the software and create scripts to make changes automatically. “We are still currently in that phase,” he says.

The third phase, he says, is anticipating the idea of artificial intelligence and generative design. “Machines are learning how we use the design tools, suggesting solutions and creating assumptions based on the user’s previous preferences.” He likens this to Amazon, for example, suggesting books based on previous purchases. “I think the creative industry is still okay. The machines work only on data we give to them and still won’t come up with the creative concepts that a human mind can. “If this technology allows users to automate certain tasks, then that task will be redundant. This will provide more space for designers to focus on the important questions.”

Click Here to return to the home page for more articles.